Fighting the Sixth Mass Extinction: GONE GLOBE

April 26, 2016

Apocalypticists predict the world will end in a ball of burning ash and fire with the eruption of the Yellowstone supervolcano. While that cataclysmic event is unlikely to happen in the next one to two million years, a supervolcano explosion in Siberia did wipe out 85 percent of land species and 95 percent of ocean species 252 million years ago. The catastrophe, nicknamed “The Great Dying,” marked one of Earth’s five mass extinctions.

It won’t take a supervolcano to create the sixth mass extinction. It’s happening right now—and scientists seem to agree that humans are causing it.

While the sixth mass extinction has been underway for centuries, a 2015 study by Stanford scientists brought the issue to the media limelight. The team of researchers claim to have proved that the sixth mass extinction is underway using relatively conservative estimates.

They found that, on average, vertebrate species are going extinct at approximately 114 times the average “background” rate, which is generally considered to be 0.1 – 1.0 extinctions per 10,000 vertebrate species every 100 years. Invertebrates, whose populations are more difficult to study yet comprise over 99 percent of Earth’s diversity, may be in greater peril. While most mass extinctions take thousands of years to reach such alarming rates, this one has managed to proliferate in a few centuries, thanks to the efforts of man.

As the study’s co-author Paul Ehrlich said to the BBC, “We are sawing off the limb that we are sitting on.”

The study concludes that mankind triggered this mass extinction through hunting, pollution and habitat loss. Some scientists even trace it back to the spread of homo sapiens across the world.

“There is some evidence that…when humans colonized the different continents, the megafauna were wiped out within a relatively short period,” said Angela van Doorn, the lab director for American University’s environmental science department. “I think there is some good evidence to support that large-bodied, slow animals were wiped out.”

Today, amphibians are the animal class most at risk; in her novel, “The Sixth Extinction,” author Elizabeth Kolbert explained that amphibian extinction rates could be 45,000 times higher than the average background rate. Their rapid loss is the result of a fungus that humans helped spread around the world.

With mammals dying at 20 to 100 times the rates of the past, there could be a dinosaur-level extinction in only 250 years. The resulting collapse of ecosystems would mean game-over for humans.

***

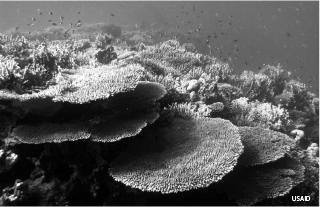

All around the globe, mass graves marked by twisting white fans of stalactites rise up from the ocean floor. These graveyards, the same color as bones, not only mark dead bodies—they are made from the dead themselves, the bleached exoskeletons of coral reefs.

As climate change heats up the oceans, coral exposed to increasing water temperatures becomes stressed, expelling a vital algae called zooxanthellae from within its tissues. This strips coral of their brilliant coloring. Although coral can survive bleaching, they need zooxanthellae, which provide about 90 percent of their energy, to grow and reproduce. Without it, coral are exposed, weak and prone to starve. Just four weeks of a one degree Celsius increase in ocean temperature can trigger bleaching, according to The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority.

Replacing reefs is harder than ever before. As the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere increases, so too does carbonic acid in ocean waters.

“As CO2 gets dissolved into the ocean water, it turns into an acid called carbonic acid, the same stuff that’s in your can of Coca-Cola,” said Kiho Kim, the environmental science department chair at AU. “And that Coca-Cola has a detrimental impact on corals, which are made of limestone, which dissolve in the presence of acid.”

Because of this, coral reefs are the most at-risk ecosystems in the world. Half of the world’s coral species have been destroyed in the last 50 years, and at this rate, the rest may be gone before the end of the 21st century.

Aside from amphibians, coral is more endangered than any terrestrial group of organisms on the planet. And losing the coral means losing the oases in what are effectively ocean deserts.

“Coral reefs are like a train station,” Kim said. “Species come in, they do their thing and then they leave. But when that train station is gone, things don’t have a place to ‘complete their destination.’”

Because ocean ecosystems are linked to terrestrial systems through the carbon cycle, loss of ocean life disrupts the entire planet.

***

Climate change has ripple effects on nearly every ecosystem. Global warming also instigates migration of species around the globe, leading to the spread of invasive species that disrupt the balance of ecosystems and destroy indigenous wildlife.

While migration is a natural phenomenon, deforestation and desertification complicate the process. As forests shrink into small fragmented pockets, tree species that would normally migrate toward cooler climates have nowhere to go. They’re stuck.

“In the past they’ve always—if it didn’t drive them to extinction—moved northwards,” van Doorn said of the stuck species. “They moved up mountains. But now with human development, they don’t have anywhere to go. I think that’s the biggest thing ahead of us.”

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) found that between 2000 and 2010, 13 million hectares of forest were affected by deforestation per year. This not only means a loss of biodiversity, but of natural resources and a vital link in the carbon and water cycles. According to the World Wildlife Fund, because forests absorb and store carbon dioxide, deforestation is the third largest source of greenhouse gas emissions behind oil and coal, responsible for 15 percent of the world’s emissions. And without trees and plants sucking up ground water and releasing it into the atmosphere through transpiration, the rain disappears. Local climates dry up.

Trees also prevent soil erosion. Fewer forests means less arable land for farming and more mudslides. And for those who rely on the goods of the forests for their livelihoods rather than farming, their natural resources disappear along with the habitat.

“People don’t understand—especially people in the U.S. who are not experiencing desertification or drought—the connection to climate change,” said Anthony Bucci III, a public affairs and media intern at the United Nations Foundation. Bucci’s work at the UN supports the Earth To Paris initiative, which raises public awareness about climate change in time for the 2015 Paris Climate Conference this December.

Consumerism plays a part too. Every purchase has an impact, with the materials coming from some natural source. While making sustainable choices is important, some worry that with the increasing rates of global population growth, greenhouse gas emissions and biodiversity loss, telling people to conserve water and recycle may not be enough.

“Some people argue, ‘Forget those small steps, it’s too late for them; we need to do something drastic,'” Kim said. “I don’t think it’s either/or. You have to do both. You have to set the culture of doing things and being aware of what the impacts of your actions are.”

***

In 2015, the UN unveiled 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) meant to build off the momentum of the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) that spanned from 2000 to 2015. Only one MDG focused on the environment: Goal 7—ensure environmental sustainability. In contrast, six of the SDGs focus specifically on sustainability and the environment.

“With the SDGs, one of the most exciting parts of them is that they were deliberately crafted to be interconnected with one another,” Bucci said. “There are some that will be more challenging than others, but that’s the nature of issues like climate change: that they touch on everything.”

The SDGs, like the MDGs, are ambitious. One goal, for example, aims to promote sustainable management of all types of forests, halt deforestation and restore degraded forests by 2020. Some, however, are skeptical of the impact the goals will actually have.

“They seem really lofty and I want to know is how do you make sure that countries are accountable for these?” van Doorn said. “If they’ve signed them or agreed to them, what does that mean?”

Bucci said that countries are not merely signing onto the UN’s proposal, but were integral in developing the SDGs.

“These SDGs were developed through an extensive multi-year process in which there was a deliberate effort to make sure that communities from around the world, from the smallest communities and local efforts to international organizations and countries, submitting their own ideas about what the SDGs should be,” he said. “So I wouldn’t necessarily say that it’s top-down, but that everyone was a part of that.”

While FAO data shows that the MDG Goal 7 had some success, especially pertaining to increasing the conservation of forests, Bucci believes that the SDGs stand an even better chance.

“We wanted to make them interconnected and wanted to make them really idealistic,” Bucci said.“We wanted to make them things that were not always high-in-the-sky, but also achievable and measurable and that we could set as goals to work towards.”

***

Scientists vary in their current extinction rate predictions (Kolbert cites a critical 2004 study that predicted anywhere from 10 to 52 percent of the world’s species could go extinct), though most agree that people need to act fast.

According to the Stanford study, avoiding the extinction means a rapid, intensified effort to save threatened species and mitigate the effects of habitat loss, climate change and overexploitation for economic gain.

“There are reasons to be hopeful,” Kim acknowledged. Still, he’s not convinced.

“I’m not terribly optimistic about the long term outlook,” he said. “The best case scenario is that we have small pockets of reasonably intact coral reef ecosystems in fairly isolated places around the world.”

Van Doorn is equally worried.

“I think there are species that are really doomed to extinction at this point because they have such small numbers,” she said.

Bucci, on the other hand, believes the UN SDGs will play an important role in saving biodiversity.

“The current period of extinction is deeply worrying,” he said. “Embracing the SDGs and taking ambitious yet practical actions will certainly have an impact on mitigating this current extinction event.”

International organizations such as the UN do have an important role to play by participating in global agreements.

“I think that if you put something together that said ‘Oh we’re going to try to prevent 10 percent of the [world’s] biodiversity loss,’ or something more realistic, maybe it would have a hard time to get people to rally behind it,” van Doorn said. “So maybe it’s better to have some lofty goals and you know at least you can make some action towards them.”

For Kim, the agreements that international organizations create matter.

“Nobody wants to feel paralyzed about not being able to change the climate.”

Bucci finds value in tackling climate change through multiple international agreements. He believes that in addition to the UN SDGs, the Paris Climate Conference this December has a big part to play in making the world care about and work towards sustainability.

“This is the beginning of a centuries-long conversation on how we as humans will live symbiotically with the environment,” he said.

“What Paris needs to be is the moment that humanity took control of its destiny. A sort of, ‘Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall,’ of the climate movement.”